June 22, 2013

Authentic printings of Declaration of Independence featured in Rebels With A Cause exhibit at Loyola in New Orleans

Just in time for Independence Day, the Loyola University New Orleans Honors Program is displaying authentic printings of the Declaration of Independence from 1776 and the real-life famous signature of John Hancock, one of America’s founding fathers. “Rebels With a Cause,” a free and public exhibit, offers a look at more than 30 rare, historical documents from June and July 1776 to 1788—the key period for the nation’s independence.

The exhibit runs through Aug. 2 and is located in the University Honors suite on the first floor of Loyola’s J. Edgar and Louise S. Monroe Library.

Loyola Honors Program Director Naomi Yavneh Klos, Ph.D., and honors students Felice Lavergne, Kylee McIntyre and Mara Steven will also host a symposium and Q-and-A session July 2 at the exhibit. The symposium will offer an overview of the documents on display and cover common myths and little-known facts surrounding America’s independence, including whether Betsy Ross designed the first flag, who the heads of state were before George Washington, the real birthday of the nation and more.

The historic documents include part of the personal collection of Yavneh Klos and her husband, Stanley Klos. The newspapers, manuscripts and letters from key storytellers such as Hancock, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Robert Morris and Henry Knox help paint the picture of America’s freedom.

“Now it’s true, you can go online and you can see the Declaration of Independence and other historical documents. But to me there’s something really palpable and special about being with the document and realizing that this was one of the most important moments in our country’s history—this is the founding of our country,” Yavneh Klos said.

“And there are all sorts of strange and quirky little stories that come out in these documents … it’s really not the way you read about these events in textbooks.”

For example, many don’t know that the Resolution for Independency (the exhibit will feature John Dunlap’s official printing of this from 1776) was actually passed July 2. Two days later, the now-famous Declaration of Independence was enacted July 4, 1776. Founding father John Adams thought July 2 would be celebrated as America’s Independence Day rather than July 4—which is what he wrote to his wife Abigail at the time, according to Yavneh Klos. Other than by Continental Congress President Hancock and Secretary Charles Thompson, the Declaration was not signed until Aug. 2.

Students and Teachers of US History this is a video of Stanley and Christopher Klos presenting America's Four United Republics Curriculum at the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School. The December 2015 video was an impromptu capture by a member of the audience of Penn students, professors and guests that numbered about 200. - Click Here for more information

The exhibit focuses on 18th-century documents describing seven important events for the nation’s freedom, including the establishment of Flag Day June 14, 1777; Spain declaring war on Great Britain June 21, 1779, which brought Louisiana into the war; Congress fleeing the capital in Philadelphia relocating to Nassau Hall in Princeton, N.J., June 21, 1783 to July 3, 1783; the ratification of the Constitution of 1787 June 21, 1788; the Resolution for Independency and the Declaration of Independence July 2, 1776 to Aug. 2, 1776; U.S. President-elect Samuel Johnston declining the office on July 9, 1781; and the Northwest Ordinance of July 13, 1787, which prohibited slavery in the U.S. territory northwest of the Ohio River.

The exhibit is open during summer library hours, which are listed online. Please contact Mikel Pak, associate director of public affairs, for media interviews at 504-861-5448.

To tell the story of the U.S. Founding, the University Honors Program presents a non-partisan exhibit illuminating historic events that occurred between 1774 and 1788, during the founding of the United States of America. The key storytellers are thirty 18th Century rare documents, manuscripts, and letters on loan from private collections throughout the United States.

Dr. Naomi Yavneh Klos, July 3rd, 2013, interview on the set of CBS Morning News

The exhibit is free and open to the public from Flag Day, June 14th, 2013 until August 2, 2013, the day prescribed by the Continental Congress for Delegates signed the engrossed Declaration of Independence. The exhibit can be viewed from 9am until 7pm at the Loyola University Honors Suite at the Monroe Library in New Orleans.

Media Alert

Media Alert

July 2nd, 2015

New Orleans, Louisiana

After 102 Years, The Federal Government Finally Agrees: Samuel Huntington And Not John Hanson Was The First USCA President to Serve Under The Articles of Confederation.

Historian Stanley Yavneh Klos Pleads With Maryland To Stop Funding Efforts That Purport John & Jane Hanson As The First President & First Lady Of The United States.

|

| 1776 Journals of Congress, by John Dunlap, July 2, 1776 entry |

The exhibit features 18th-Century primary sources reporting on seven June and July events:

|

| Dr. Naomi Yavneh Klos, July 3rd, 2013, on the set of CBS Morning News presenting Rebels With A Cause |

- John Dunlap’s official printing of the 1776 Journals of Congress opened to the July 2nd Resolution for Independency and the July 4th, 1776 Declaration of Independence.

- Dunlap facsimile printing of the Declaration of Independence that was featured by the Freedom Train on its nationwide tour from April 1975 - December 1976 and was seen in 76 cities in the 48 contiguous states during the Bi-Centennial celebration.

- The Pennsylvania Packet, July 8, 1776, Centennial Edition, with the entire text of the Declaration of Independence printed on page one.

- Various Signed letters and documents from numerous signers of the Declaration of Independence including John Hancock and Thomas Jefferson.

- John Dunlap’s official printing of the 1777 Journals of Congress opened to the June 14, 1777 Resolution establishing the first flag of the United States.

- Acts Passed at the First and Second Sessions of the Fifteenth Congress opened to the Act to establish the Flag of the United States that changed the flag to 20 stars, with a new star to be added when each new state was admitted, while the number of stripes was reduced to 13 to honor the original states, April 4, 1818

- 13 Star Flag sewn for the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876, the first official World's Fair in the United States held in Philadelphia.

- 1763 printing of the Definitive Treaty of Friendship of Peace between his Britannick Majesty, the Most Christian King, and the King of Spain, Concluded at Paris, the 10th day of Feb., 1763 that turned over Florida and eight Louisiana parishes to Great Britain.

- Autograph Letters signed by King George III and Queen Charlotte, who were the monarchs of British Colonial America.

- 1780 printing of Major General Campbell's account of the surrender of Baton Rouge and numerous Florida towns east up to Pensacola led by Governor, Don Beraud de Galvez.

- The 1803 Acts of Congress open to the dual language printing of the Louisiana Purchase Treaty signed Commissioners James Monroe and Robert Livingston.

- Louisiana Territory William C.C. Claiborne autograph document signed displayed with the new Governor's Address to the Citizens of Louisiana dated December 20, 1803.

- 1781 Journals of the United States in Congress Assembled published by John Patterson and opened to Samuel Johnston’s presidency election, the entry on his declining the office, and the subsequent election of Thomas McKean as second President of the United States under the Articles of Confederation.

- Rare Henry Knox, Secretary of War document signed by Samuel Johnston as North Carolina’s first US Senator.

- President Thomas McKean September 29, 1781 letter to New Hampshire General John Stark regarding the dollar’s rampant depreciation and his military pay.

Congress Flees Philadelphia - The United States in Congress Assembled, under threat of a US Army Mutiny, relocates the Seat of Government from Independence Hall to Nassau Hall in Princeton, New Jersey - June 21st, 1783, to July 3rd, 1783.

- Proclamation issued by Elias Boudinot, as President of the United States in Congress Assembled on June 24, 1783 explaining the necessity of abandoning Independence Hall, due to a US Army mutiny, and the necessity of relocating the US Seat of Government to Nassau Hall in Princeton New Jersey.

- President Elias Boudinot autograph letter signed to Major General Arthur St. Clair stating that You may depend on Congress having been perfectly satisfied with your conduct acknowledging his role in extracting Congress from Independence Hall while it was surrounded by over 300 mutinous soldiers.

- An 18th Century printing of an Annis Boudinot’s Poem, the wife of NJ Signer Richard Stockton and sister of President Elias Boudinot, who was instrumental in her brother’s decision to move the US Seat of Government to Princeton.

The Northwest Ordinance - An Ordinance for the government of the Territory of the United States northwest of the River Ohio - July 13th, 1787

- August 1787 full printing of the Ordinance for the government of the Territory of the United States northwest of the River Ohio.

- In accordance with Article V of the Northwest Ordinance, exhibited is the Ohio Enabling Act of 1802 entitled: An Act To Enable The People Of The Eastern Division Of The Territory North-West Of The River Ohio, To Form A Constitution And State Government, And For The Admission Of Such State Into The Union, On An Equal Footing With The Original States, And For Other Purposes.

- In accordance with Article VI of the Northwest Ordinance, exhibited is a Deed of Emancipation autograph document signed by David Enlow freeing his slave Sarah on September 20, 1807 meeting the no slavery requirement in the new Territory of Indiana.

The Ratification of the Constitution of 1787 - June 21st, 1788

- October 1787 printing of the United States Constitution framed in Philadelphia by the delegates of 12 States on September 17, 1787.

- July 3, 1788 Newspaper account of the Portsmouth Parade celebrating 9th State, New Hampshire, ratification dissolving the Articles of Confederation and enacting the Constitution of 1787 along with a the state’s Bill of Rights recommendations.

- August 1788 Pamphlet printing an Eleven State Ratification table printed with ratification resolutions of New Jersey, Maryland, South Carolina, New Hampshire, Virginia and New York. Also printed are numerous State amendments to the US Constitution of 1787, including New York’s 32 Amendments and Virginia’s Declaration of Rights with its 21 proposed Amendments.

Colonial American Documents

Phélypeaux, Louis comte de Pontchartrain - A rare 1698 document signed printed on a 10”x 13” parchment and signed by Phélypeaux Comte de Pontchartrain. The document is the receipt for the Lord of the Morandière signed by Pontchartrain as the Crown’s Controller-General of Finances. One year later, in 1699 Pontchartrain became Louis XIV’s Chancellor of France. Most notably Pontchartrain’s name is given to the lake of Pontchartrain, New-Orléans during the French colonization of Louisiana.

[King Louis XIV] (Namesake of Louisiana) - Gentleman's Magazine - September 1750, URBAN, Sylvanus, E. Cave, 1750. Soft cover. Book Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. 1st Edition. USOG-2: A small booklet, pp 386-432 plus the cover Anecdotes on Louis XIV by the celebrated M. de Voltaire, Boston Reports from, "Halifax Nova Scotia, and Boston in New England July 10, 1750, ... Governor Cornwallis hath issued a proclamation, offering a reward of 50 pds... to any person that shall bring in an Indian prisoner, or the head or the scalp of an Indian killed in the province of Nova Scotia, or Accadie, to be paid out of the treasury." The account of the Conversion of Daniel Tnangam Alexander, an Eminent Jew to the Protestant Religion. Adscription of a Venomous Serpent with plate from Sweden. The Magazine is in good condition, size, 5 x 8 inches. - Klos Yavneh Academy Collection

Royal Orléans House - manuscript recording the payment of “portion of pension" for the benefit of Sieur Hennequin. The Duke d'Orléans has boldly signed the manuscript L. Philippe of Orléans. The fragile 1752 manuscript, which measures 9 ½ x 14 ½, also has the signature of Etienne de Silhouette who was a French Controller-General of Finances under Louis XV.

New Orleans is named after the Royal House of Orléans in honor of Philip II, Duke of Orléans who served as the Regent of France, 1715 to 1723. All the Orléans descended in the legitimate male line from the dynasty's founder, Hugh Capet. It became a tradition during France's ancient régime for the duchy of Orléans to be granted as an appanage to a younger (usually the second surviving) son of the king. While each of the Orléans branches thus descended from a junior prince, they were always among the king's nearest relations in the male line, sometimes aspiring and sometimes succeeding to the throne itself. - Klos Yavneh Academy Collection

ROSS, GEORGE - Autograph document signed “Geo. Ross,” dated “January Term 1750.” A response to a summons for Nathaniel Simpson of Cumberland County, Pennsylvania to appear regarding money owed to Jacob Snevley. George Ross as attorney for Nathaniel Simpson writes his rebuttal on one page. - Klos Yavneh Academy Collection

GALLOWAY, JOSEPH - Document SIGNED. Manuscript D.S. "Joseph Galloway" one page folio vellum, Philadelphia, July 12, 1754 in which he witnesses a deed between Samuel Preston Moore and Benjamin Loxley for a "...Strip or piece of Ground on the North side of Mulberry street...". Joseph Galloway (1731 - 1803), Philadelphia attorney, Loyalist member of the Pennsylvania Assembly (1757-75) and First Continental Congress and intimate friend of Benjamin Franklin. In an attempt to avert the break with Great Britain, he proposed The Galloway Plan for self-government while maintaining allegiance to England. Suggesting that all legislation affecting colonies be approved by both Parliament and a Grand Council representing American states, it was rejected in the Continental Congress by one vote. When the British occupied Philadelphia in 1777, he was appointed city administrator. Galloway moved to London when the military abandoned the city the following spring. The Pennsylvania assembly in 1788 convicted Galloway of high treason, and ordered the sale of his estates. - Klos Yavneh Academy Collection

[KING GEORGE III] Marriage Declaration of King George III dated July 8, 1761 that “I have, ever since my accession to the throne, turned my thoughts towards the choice of a princess for my consort …I come to a resolution to demand in marriage the princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg Strelitz; a princess distinguished by every eminent virtue." The London Magazine or Gentleman’s Monthly Intelligencer, July 1761, R. Baldwin, London - Klos Yavneh Academy Collection

[BRITISH FLORIDA & LOUISIANA] - 1763 - Gentleman's Magazine Account of British Florida/Louisiana - with color map. NOTE: The Florida Parishes (Spanish: Parroquias de Florida, French: Paroisses de Floride), also known as the North Shore region, are eight parishes in the southeastern part of the U.S. state of Louisiana, which were part of West Florida in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Unlike much of Louisiana, this region was not part of the Louisiana Purchase, as it had been under British and then Spanish control. The parishes are East Baton Rouge, East Feliciana, Livingston, St. Helena, St. Tammany, Tangipahoa, Washington, and West Feliciana. The United States annexed most of West Florida in 1810. It quickly incorporated the area that became the Florida Parishes into the Territory of Orleans, which became the U.S. state of Louisiana in 1812. - Klos Yavneh Academy Collection.

DUNLAP, JOHN - Manuscript Colonial bail bond of John Dunlap and Alexander McBride payable to John Holmes for the sum of 40 Pounds current money of Pennsylvania and dated 1766. The bond is conditional upon Dunlap’s appearance in court. Size 9" by 13" on laid, watermarked (crown over GR), rag-content paper; age toned, tiny holes - Klos Yavneh Academy Collection.

RANDOLPH, PEYTON & BLAIR, JOHN sign a March 4, 1773 Virginia Five Pound Colonial Note. The note, legal tender in Virginia, is also signed by future Constitution of 1787 signer and Supreme Court Justice John Blair. - Klos Yavneh Academy Collection

The First United Republic: United Colonies of America

Thirteen British Colonies United in a Continental Congress

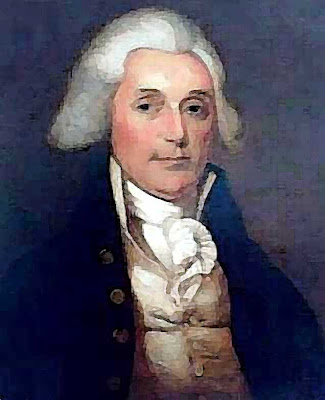

First United American Republic: United Colonies of America: Thirteen British Colonies United in Congress (September 5th, 1774 to July 1st, 1776) was founded by 12 colonies under the First Continental Congress and expired under the Second Continental Congress. King George and Queen Charlotte welcome visitors in an oil painting gallery. The section includes 18th-Century letters and manuscripts of United Colonies Continental Congress Presidents Peyton Randolph, Henry Middleton, and John Hancock. Exhibit options include:

[SUFFOLK RESOLVES] - November 1774 historic printing headed: "Account of the Proceedings of the American Colonies since the passing the Boston Port Bill."Other content includes: "Debates in the House of Commons" relative to the situation in America. Another report is headed: "Causes of the Present Discontent & Commotion in America" which includes a list of 13 reasons, the first of which reads: "The stamp act, by which duties, customs & impositions, were enacted without & therefore against, the consent of the colonies..." Urbanus, Sylvanus, The Gentleman's Magazine, and Historical Chronicle, November 1774 - Klos Yavneh Academy Collection

Griffin, Cyrus autograph letter signed dated October, 1774, to Burgess Ball concerning the birth of his daughter Mary and the family seeking passage from London to Virginia. In 1774, Cyrus Griffin and Lady Christina bore a second child, Mary. Historians are not sure how long the couple remained in London. In this letter Griffin writes. "My wife is now safely delivered of a stout girl and continues at present very hearty and shall be prepared for the first ship." - Klos Yavneh Academy Collection

[ARTICLES OF ASSOCIATION] - Very Rare Colonial Printing of the Articles issued October 20, 1774 and recorded in Extracts From The Votes And Proceedings Of The American Continental Congress, Held At Philadelphia, On The 5th Of September, 1774 Containing The Bill Of Rights, A List Of Grievances, Occasional Resolves, The Association, An Address To The People Of Great-Britain, And A Memorial To The Inhabitants Of The British American Colonies. Published By Order Of The Congress. Philadelphia : Printed. Hartford: Re-printed by Eben. Watson, near the Great-Bridge, [1774] - Klos Yavneh Academy Collection.

[MIDDLETON, HENRY] - Address of the American Delegates to Quebec – Urbanus, Sylvanus, The Gentleman's Magazine, and Historical Chronicle from Supplement. London: D. Henry, 1774. This volume, 8” x 9½” , includes a full printing of first Continental Congress’ “Substance of the Address of the American Delegates, in general Congress assembled, to the inhabitants of the province of Quebec.” signed in type Henry Middleton, President. - Klos Yavneh Academy Collection

[FRANKLIN, BENJAMIN] - "Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union entered into by the Delegates of the several Colonies of New Hampshire, &c in General Congress met at Philadelphia, May 10, 1775." [Philadelphia, ca.21 July 1775]. THE GENTLEMAN'S MAGAZINE, London, December, 1775, two page 1775 printing on what is commonly known as the Benjamin Franklin version of the a plan to unite for: "...a firm league of friendship with each other...for their prosperity, for their common defence against their enemies, for the security of their liberties & properties...". The wording in this version of the Articles of Confederation involves some different text from the May 1775 Benjamin Franklin version due to the constitution’s evolution into the final version of the Articles passed November 15, 1777. -- Loan Courtesy of Klos Yavneh Academy

[BUNKER HILL] - The first report on the battle of Bunker Hill, which is signed in type: Thomas Gage. This report takes nearly an entire page and begins: "I am to acquaint your Lordship of an action that happened on the 17th of June instant between his Majesty's troops and a large body of the rebel forces. An alarm was given at break of day on the 17th...The loss the rebels sustained must have been considerable from the great numbers they carried off during the time of action & buried in holes..." with much further particulars. Also in this GENTLEMAN'S MAGAZINE, London, July, 1775 issue are: "Friendly Address to Lord North" which is on American affairs, A lengthy "Proclamation by Hon. Th. Gage, Commander in Chief of His Majesty's Province of Mass. Bay" that offers a pardon to those who lay down their arms & return to being peaceable subjects, excepting Samuel Adams & John Hancock. "Proceedings of the American Colonists since passing the Boston Port Bill" takes over 5 pages & has some good talk on St. Johns, Ticonderoga & events at Crown Point including mention of Benedict Arnold: "...We overtook Col. Arnold in the boat, took him on board..." The Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Chronicle, Urbanus, Sylvanus, July 1775, London: D. Henry, 1775. - Klos Yavneh Academy Collection

[OLIVE BRANCH PETITION] - British September 1775 printing of "Petition of the American Congress to the King” was the last effort of the Continental Congress to avoid war with Great Britain in 1775. Some delegates to the Continental Congress wanted to break with England at this time, but they yielded to the majority who weren't ready yet. Those who were more moderate wanted to explain their position clearly to King George, in hopes that he had been misinformed about their intentions. They made it clear that they were loyal subjects to Great Britain and they wanted to remain so, as long as their grievances were addressed. The king eventually refused to even receive their petition, which eventually came to be known as "The Olive Branch Petition." This is a full printing of the Petition which concludes “That your Majesty may enjoy a long and prosperous reign, and that your descendants may govern your dominions with honor to themselves and happiness to their subjects is our sincere and fervent prayer. JOHN HANCOCK [Signed by all the Delegates]” Printing from Gentleman’s Magazine - Klos Yavneh Academy Collection

[OATH OF SECRECY] - November 9, 1775, Resolved: That every member of this Congress considers himself under the ties of virtue, honor and love of his Country, not to divulge, directly or indirectly, any matter or thing agitated or debated in Congress, which the majority of the Congress shall order to be kept secret, and that if any member shall violate this agreement, he shall be expelled this Congress, & deemed an enemy to the liberties of America, & liable to be treated as such; FORCE, Peter, American Archives: Collection of Authentick Records, for the United States, to the Final Ratification thereof. Published Under Authority of an Act of Congress in 1848 - Klos Yavneh Academy Collection.

[COMMON SENSE] – 18th Century printing of Thomas Paine’s January 1776 Common Sense, open to his recommendations for formulating a plan for the new government: “If there is any true cause for fear respecting independence , it is because no plan is yet laid down. Men do not free their way out … I offer the following hints … Let the assemblies be annual with a president only. The representation more equal. Their business wholly domestic, and subject to the authority of a Continental Congress. Let each colony be divided into six, eight or ten convenient districts, each district to send a proper number of delegates to congress … the whole number in congress to be at least 390… “ The American Museum, or Repository of Ancient and Modern Fugitive Pieces, &c. prose and poetical. February, 1787. Volume I., Number II. Philadelphia: Mathew Carey, 1787, 8vo. - Klos Yavneh Academy Collection

ELLSWORTH, OLIVER - Rare Revolutionary Era document signed O. Ellsworth and dated, Hartford, June 7th 1776, approving payment of Twenty Pounds, three shillings & seven pence for Salt Peter, a component of gunpowder, for the Colony of Connecticut. - Klos Yavneh Academy Collection

Resolved, that these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent states, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the state of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved. [2]

|

| Dr. Naomi Yavneh Klos, July 3rd, 2013, on the set of CBS Morning News displaying and explaining the July 2nd, 1776, Resolution for Independency. |

John Adams wrote Abigail Adams on July 3, 1776:

Yesterday the greatest Question was decided, which ever was debated in America, and a greater perhaps, never was or will be decided among Men. A Resolution was passed without one dissenting Colony "that these united Colonies, are, and of right ought to be free and independent States, and as such, they have, and of Right ought to have full Power to make War, conclude Peace, establish Commerce, and to do all the other Acts and Things, which other States may rightfully do.

You will see in a few days a Declaration setting forth the Causes, which have impell'd Us to this mighty Revolution, and the Reasons which will justify it, in the Sight of God and Man. A Plan of Confederation will be taken up in a few days. On July 2, 1776 the Association known as United Colonies of America officially became the United States of America .[ix]

Consequently, it was the date of July 2, 1776 that John Adams thought would be celebrated by future generations of Americans writing to his wife Abigail Adams a second letter on July 3, 1776:

But the Day is past. The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America.

I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.

You will think me transported with Enthusiasm but I am not. -- I am well aware of the Toil and Blood and Treasure, that it will cost Us to maintain this Declaration, and support and defend these States. -- Yet through all the Gloom I can see the Rays of ravishing Light and Glory. I can see that the End is more than worth all the Means. And that Posterity will tryumph in that Days Transaction, even altho We should rue it, which I trust in God We shall not. [x]

Was Delaware, Virginia, or New Hampshire the first US State?

Declaration of Independence - Exhibited here is the Pennsylvania Packet, July 8, 1776, with the entire text of the Declaration of Independence printed on page one of the four page newspaper. The following day, July 9th, New York would approve the resolution making the Declaration of Independence unanimous.

When most Americans picture the Declaration, they envision the engrossed manuscript signed by John Hancock and 55 others, titled “The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen United States of America.” But what they are seeing is a document that was not written or signed in July 1776. When the delegates agreed to the final text of the Declaration on July 4th, New York abstained. As seen in this newspaper, the original heading was "A Declaration by the Representatives of the United States of America, in General Congress assembled." The Declaration was then signed on July 4th only by John Hancock and Continental Congress secretary Charles Thomson, and sent to press. The heading was changed later in July once New York added its assent, and on August 2, members of Congress met and signed the engrossed copy of the Declaration and did not become familiar to Americans until decades later.

The Pennsylvania Packet, July 8, 1776 centennial printing of the Declaration of Independence reflects the experience of everyday Americans as they read news of independence for the first time during that momentous July of 1776.

|

|

Engrossed Declaration of Independence, William J. Stone, Copperplate engraving on vellum, First Edition. 24 3/4 x 30 5/16”.

Historical Background: On July 19, 1776, ten days after New York approved the Declaration of Independence, the Continental Congress ordered an official copy of the Declaration to be engrossed on vellum and signed by the members. Timothy Matlack, the clerk of Continental Congress Secretary Charles Thomson, was chosen to hand write the text of the Declaration onto a large vellum sheet, which would then be signed by the delegates. The title of Declaration of Independence by the Representatives of the United States of America in General Congress Assembled was changed to “The Unanimous Declaration of the Thirteen United States of America.”.

On August 2, 1776, it was recorded in the Journal of Congress that “the declaration of independence being engrossed and compared at the table was signed” by the members of Congress then assembled. According to the -- National Archives and Records Administration:

John Hancock, the President of the Congress, was the first to sign the sheet of parchment measuring 24¼ by 29¾ inches. He used a bold signature centered below the text. In accordance with prevailing custom, the other delegates began to sign at the right below the text, their signatures arranged according to the geographic location of the states they represented. New Hampshire, the northernmost state, began the list, and Georgia, the southernmost, ended it. Eventually 56 delegates signed, although all were not present on August 2. Among the later signers were Elbridge Gerry, Oliver Wolcott, Lewis Morris, Thomas McKean, and Matthew Thornton, who found that he had no room to sign with the other New Hampshire delegates. A few delegates who voted for adoption of the Declaration on July 4 were never to sign in spite of the July 19 order of Congress that the engrossed document "be signed by every member of Congress.

Non-signers included John Dickinson, who clung to the idea of reconciliation with Britain, and Robert R. Livingston, one of the Committee of Five, who thought the Declaration, was premature.

When Congress took flight to Philadelphia from Baltimore in March 1777, the manuscript Declaration traveled along. The Declaration remained with the Continental Congress moving back to Philadelphia, then to Lancaster, then to York, and finally back to Philadelphia where it was unveiled for the March 1, 1781 ratification ceremonies of the Articles of Confederation.

The document remained in Philadelphia with the new Us Constitutional body, the United States in Congress Assembled (USCA), until June 1783 when Congress fled to Princeton in the wake of 400 mutinous soldiers surrounding Independence Hall. The Declaration then mad the trek with the USCA to Annapolis in 1784, to Trenton in 1785, and then to New York in 1786 where it remained until the second Constitution was ratified and the new government was made operational. On December 6, 1790, the United States Capital officially moved from New York City to Philadelphia taking the Declaration of Independence with it until another move in 1800 when the capitol was permanently settled in Washington, D.C.

During this period, the Declaration was frequently unrolled for display to visitors, and the signatures, especially, began to fade after nearly fifty years of handling. More damage followed, caused by the effects of aging and exposure to sunlight and humidity as the Declaration hung unprotected on a wall in the Patent Office for thirty-five years.

In 1820, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams grew concerned over the fragile condition of the Declaration. With the approval of Congress, Adams commissioned William J. Stone to engrave a facsimile—an exact copy—on a copper plate. Stone’s engraving is the best representation of the Declaration as the manuscript looked prior to its nearly complete deterioration. Stone used a "new" Wet-Ink Transfer process. Unfortunately this Wet-Ink Transfer greatly contributed to the degradation of the only engrossed and signed Declaration of Independence ever produced. On April 24, 1903 the National Academy of Sciences reported its findings, summarizing the physical history of the Declaration:

The instrument has suffered very seriously from the very harsh treatment to which it was exposed in the early years of the Republic. Folding and rolling have creased the parchment. The wet press-copying operation to which it was exposed about 1820, for the purpose of producing a facsimile copy, removed a large portion of the ink. Subsequent exposure to the action of light for more than thirty years, while the instrument was placed on exhibition, has resulted in the fading of the ink, particularly in the signatures. The present method of caring for the instrument seems to be the best that can be suggested. The committee does not consider it wise to apply any chemicals with a view to restoring the original color of the ink, because such application could be but partially successful, as a considerable percentage of the original ink was removed in making the copy about 1820, and also because such application might result in serious discoloration of the parchment; nor does the committee consider it necessary or advisable to apply any solution, such as collodion, paraffin, etc., with a view to strengthening the parchment or making it moisture proof. The committee is of the opinion that the present method of protecting the instrument should be continued; that it should be kept in the dark, and as dry as possible, and never placed on exhibition.

The Wet-Ink Transfer Process called for the surface of the Declaration to be moistened transferring some of the original ink to the surface of a clean copper plate. Three and one-half years later under the date of June 4, 1823, the National Intelligencer reported that:

the City Gazette informs us that Mr. Wm. J. Stone, a respectable and enterprising (sic) engraver of this City has, after a labor of three years, completed a facsimile of the Original of the Declaration of Independence, now in the archives of the government, that it is executed with the greatest exactness and fidelity; and that the Department of State has become the purchaser of the plate. The facility of multiplying copies of it, now possessed by the Department of State will render furthur (sic) exposure of the original unnecessary.

Historian and rare document dealer Seth Kaller maintains the wet ink transfer process never occurred writing that Stone “ … left minute clues to distinguish the original from the copies, also providing evidence of his painstaking engraving process. Stone’s engraving is the best representation of the Declaration manuscript as it looked at the time of signing.”

Daniel Brent of the Department of State wrote to Stone on May 28, 1823, requesting 200 copies of the facsimile “from the engraved plate…now, in your possession, and then to deliver the plate itself to this office to be afterwards occasionally used by you, when the Department may require further supplies of copies from it.” Stone proceeded to print 201 copies on vellum, one of which he kept for himself, as was customary though perhaps not authorized in this case. Four copies presently known on heavy wove paper are most likely proofs before printing on the much more expensive vellum.

On May 26, 1824, Congress provided orders to John Quincy Adams for distribution of the Stone facsimile for distribution. The surviving three signers of the Declaration, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Charles Carroll of Carrollton, each received two copies. Two copies each were also sent to President James Monroe, Vice President Daniel D. Thompkins, former President James Madison, and the Marquis de Lafayette. The Senate and the House of Representatives split twenty copies. The various departments of government received twelve copies apiece. Two copies were sent to the President’s house and to the Supreme Court chamber. The remaining copies were sent to the governors and legislatures of the states and territories, and to various universities and colleges in the United States.

All subsequent exact facsimiles of the Declaration descend from the Stone plate. One of the ways to distinguish the first edition is Stone’s original imprint, top left: “ENGRAVED by W.J. STONE for the Dept. of State by order,” and continued top right: “of J. Q. Adams, Sec of State July 4, 1823.” Sometime after Stone completed his original printing, his imprint at top was removed, and replaced with a shorter imprint at bottom left, “W. J. STONE SC WASHn,” just below George Walton’s printed signature for his second edition printings.

|

|

1776 Journals of Congress - Exhibited here is the exceedingly rare Journals Of Congress. Containing The Proceedings From January 1, 1776, To January 1, 1777, York-town, Pa.: Printed by John Dunlap, with a manuscript note relaying provenance from New Hampshire Revolutionary War Governor Meshech Weare.

This Declaration of Independence was printed by Dunlap after the Articles of Confederation were passed by the Continental Congress on November 15, 1777, the printing, exactly the same as Aiken's Journals removes the word "General" in the July 4th Dunlap Broadside title from "A Declaration of Independence by the Representatives of the United States of America in General Congress Assembled."

|

|

This volume of the Journals of Congress is one of the rarest of the series issued from 1774 to 1788, and has a peculiar and romantic publication history. Textually it covers the exciting events of 1776, culminating with the Declaration of Independence on July 4, an early printing of which appears here, as well as all of the other actions of Congress for the year. It is thus a vital document in the history of American independence and the American Revolution. Through the middle of 1777 the printer of the Journals of Congress was Robert Aitken of Philadelphia. In 1777 he published the first issue of the Journals for 1776, under his own imprint. This was completed in the spring or summer. In the fall of 1777 the British campaign under Howe forced the Congress to evacuate Philadelphia, moving first to Lancaster and then to York, Pennsylvania. The fleeing Congress took with it what it could, but, not surprisingly, was unable to remove many copies of its printed Journals, which would have been bulky and difficult to transport. Presumably, any left behind in Philadelphia were destroyed by the British, accounting for the particular scarcity of those volumes today. Among the material evacuated from Philadelphia were the printed sheets of pages 1-424 of the 1776 Journals, printed by Aitken. Having lost many complete copies in Philadelphia, and not having the terminal sheets to make up more copies, Congress resolved to reprint the remainder of the volume.

Robert Aitken had not evacuated his equipment, but John Dunlap, the printer of the original Declaration, had. Congress thus appointed Dunlap as the new printer to Congress on May 2, 1778. Dunlap then reprinted the rest of the volume (coming out to a slightly different pagination from Aitken's version). He added to this a new title page, under his imprint at York, with a notice on the verso of his appointment as printer to Congress. This presumably came out between his appointment on May 2 and the return of Congress to Philadelphia in July 1778. Because of Dunlap's name on the title page, it has often been erroneously assumed that this volume contains a printing of the Declaration of Independence by Dunlap. In fact, that appears in the section of the original Aitken printing thus it is a very rare joint endeavor between the two renowned printers. Evans has further muddied the waters by the ghost entry of Evans 15685, ascribing a Dunlap, York printing to 1777. In fact, there is only one Dunlap version, Evans 16137, with the 1778 date. -- Klos Yavneh Collection

|

Notwithstanding New York’s July 9th approval, the passage of Lee’s Resolution and even John Adams’ letter to Abigail declaring that “The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America”, [4] July 4th has been heralded as the birthdate of the United States of America since 1777. Moreover, July 4th has remained sacrosanct as the United States birthday despite the enactment of two distinctly different U.S. Constitutions in 1781 and again in 1789 that reformulated the United States’ federal government.

U.S. governmental authorities universally agree that the birth year of the current U.S. Republic is 1776 and not 1781 (when the Articles of Confederation was ratified), or 1784 (when the Treaty of Paris was ratified ending the war with Great Britain), or September 17, 1787 (when the Philadelphia Convention produced the current U.S. Constitution), or March 4, 1789, when the current tripartite system began to govern the United States of America.

It is remarkable, however, that, while July 4th, 1776, stands as the nation’s birthdate John Hancock, the Declaration's presidential signer, is passed over by the same governmental authorities as the first U.S. Head of State. Similarly, Samuel Huntington, the first President under the Articles of Confederation, is also passed over as President of the United States in America in Congress Assembled. Furthermore, The State of Delaware, which enacted the Declaration of Independence with 11 other States on July 4th, 1776 and was the 12 State to ratify the Articles of Confederation is herald as the "First State" because of its December 7, 1787 ratification of the second United States constitution passing over the July 4th history.

In contrast, these same officials recognize Benjamin Franklin as the first Postmaster General who served not under the current U.S. Constitution but under the laws of the Continental Congress. Benjamin Lincoln is recognized as the first Secretary of War being appointed in 1781 as opposed to Henry Knox who was the First Secretary of War under the current U.S. Constitution.

|

| Exhibited here is The Lady's Magazine Or Entertaining Companion for the Fair Sex, appropriated solely to their Use and Amusement, 1776 printing which contains numerous Continental Congress and Revolutionary War reports but does not print a 1776 copy of the Declaration of Independence. The Lady's Magazine does report, however, several July festivities occurring after the passage of the Declaration of Independence. |

Setting these inconsistencies aside, the question that is most pertinent to this Independence Day exhibit remains: Why does the U.S. Government, since 1777, celebrate the 4th of July as Independence Day and not the 2nd of July?

When the twelve United Colonies of America declared their independence on July 2nd the Declaration of Independence (DOI) was already before the Colonial Continental Congress for its consideration. The first draft was read before the delegates on Friday June 28, 1776, and then ordered to lie on the table over the weekend for their review. On Monday, July 1st, the DOI was read again to the “Committee of the Whole.” The DOI was debated along with the much shorter Lee Resolution.

The 12 Colonies, whose members were empowered to declare independence, were unable to garner the necessary 12 delegation votes to make the measure unanimous. Accordingly, it was decided to postpone the vote on independence until the following day, July 2nd, and the 12 colonial delegations passed the Lee’s Resolution declaring their independence from Great Britain. The DOI, however, was quite another matter; Committee of the Whole Chairman Benjamin Harrison requested more time and the members agreed to continue deliberations following day.

On July 3rd, the Continental Congress considered, debated and passed several pressing war resolutions before taking up the DOI resolution. Once again, not having sufficient time to finalize the proclamation, Chairman Benjamin Harrison requested more time and the U.S. Continental Congress tabled deliberation until the following day. On the morning of July 4, 1776 the delegates debated and passed the following war resolution: [9]

… that an application be made to the committee of safety of Pennsylvania for a supply of flints for the troops at New York: and that the colony of Maryland and Delaware be requested to embody their militia for the flying camp, with all expedition, and to march them, without delay, to the city of Philadelphia.[10]

The Continental Congress then took up, finalized, and passed the Declaration of Independence: “Mr. Benjamin Harrison reported, that the committee of the whole Congress have agreed to a Declaration, which he delivered in. The Declaration being read again was agreed to …”[11]

The Declaration of Independence proclaimed why “… these United Colonies are, and, of right, ought to be, Free and Independent States …”[12] and its content served to justify the Colonial Continental Congress July 2nd vote declaring independence. It was the rhetoric in the DOI and not Lee’s Resolution that exacted the vote for independence on July 2nd, 1776, from the 12 state delegations. Moreover, the July 4th, 1776, resolution included naming the Second United American Republic which was not incorporated in Lee’s Resolution. It is also important to note that the name, United States of America, was not utilized on any of the Continental Congress resolutions or bills passed after Lee’s Resolution on July 2nd up until the passage of the DOI on July 4th, 1776.

It is true that in Thomas Jefferson’s DOI drafts, the word “States” was substituted for “Colonies” in the stile, or name, “United Colonies of America.” It is also true that Jefferson’s substitution was in accordance with Lee’s Resolution that asserted the “United Colonies” were to be “free and independent States.” The new republic was not named the “United States,” however, until the Declaration of Independence’s adoption on July 4, 1776.

The naming of this new republic was no small matter, and the topic would be addressed again in later deliberations on the Articles of Confederation and the current U.S. Constitution. [13] As noted earlier, the 1775 Articles of Confederation and Declaration for Taking up Arms initially named the First United American Republic the United Colonies of North America. The name was only shortened by the Continental Congress to the United Colonies of America in 1776. We must, therefore, pay heed to the fact that the nation’s name was adopted on July 4th, 1776, with the passage of the Declaration of Independence and not on July 2nd with the enactment of Lee’s Resolution. This circumstance, coupled with the nearly completed Declaration of Independence being laid before the members on June 28th and present during the July 2nd vote, explicates why the 4th and not the 2nd was designated Independence Day by the Continental Congress and was accepted as such by the then future congresses of the United States of America.

[1] Hereinafter referred to as the Lee’s Resolution.

[2] Op Cit, June 7, 1776

[3] On July 9th, 1776 the New York Provincial Congress assembled in the White Plains Court House and adopted the July 4, 1776 resolution heartedly supported by John Jay who had rushed from New York City to address that body: “That reasons assigned by the Continental Congress for declaring The United Colonies Free and Independent States are cogent and conclusive, and that now we approve the same, and will at the risque of our lives and fortunes, join with the other colonies in supporting it.” - New York Provincial Congress, Resolution supporting the Declaration of Independence, July 9, 1776.

[4] Letter from John Adams to Abigail Adams, 3 July 1776. Original manuscript from the Adams Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society. “But the Day is past. The Second Day of July 1776 will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.”

[5] John Hanson, “United States in Congress Assembled Proclamation. “The Freeman’s Journal, October 16, 1782, Number LXXVII, p. 3.

[6] In the first three United American Republics, the signature of U.C. and U.S. Presidents are not required to enact any Congressional legislation. These founding presidents, unlike the current U.S. Presidents, had one vote in their respective state delegations in the “one state one vote” unicameral congressional system. In the Fourth American Republic, Article I of the Current U.S. Constitution requires every bill, order, resolution or other act of legislation by the Congress of the United States to be presented to the U.S. President for his approval. The President can either sign it into law, return the bill to the originating house of Congress with his objections to the bill (a veto), or neither sign nor return it to Congress. If he does the latter and Congress remains in session for ten days exempting Sundays, the bill becomes law. If during those ten days Congress adjourns than the bill does not become a law.

[7] Emancipation Proclamation, January 1, 1863, Original Manuscript, The Charters of Freedom, US National Archives and Records Administration.

[8] Ibid.

[9] A Committee of the Whole is a device in which a legislative body or other deliberative assembly is considered one large committee.

[10] JCC, 1774-1789, July 4, 1776

[11] Ibid.

[12] JCC, 1774-1789, July 2, 1776

[13] At the Philadelphia Convention on May 30, 1787, Virginia Governor and member Edmund Randolph moved to rename the United States, the “National Government of America.” This name would remain as part of the current U.S. Constitution draft until June 20th, 1787, when it was moved by Mr. Oliver Ellsworth, seconded by Mr. Nathaniel Gorham “… to amend the first resolution reported from the Committee of the whole House so as to read as follows -- namely, Resolved that the government of the United States ought to consist of a Supreme Legislative, Judiciary, and Executive. On the question to agree to the amendment it passed unanimously in the affirmative.” Max Farrand, The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1911.

In the United States, Flag Day is celebrated on June 14th, commemorating the adoption of the "Stars and Stripes." On this date, as recorded in the original 1777 Journals of Congress included in this exhibit, the U.S. Continental Congress passed the following resolution:

Resolved, That the flag of the thirteen United States of America be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a New Constellation.

|

June 14th, 1777, United States Flag Resolution from the first printing of ''Journals of Congress Containing The Proceedings In The Year, 1777 Published by Order of Congress by John Dunlap: Philadelphia: 1778.” The Journals of the Congress, from which this Flag Act is displayed, formed the only central record of the colonies and the subsequent states”. Printed by order of Congress, this official account is printed by John Dunlap, who in addition to issuing the first publication of the Declaration of Independence, was one of “the principal printers to Congress”. The Journal exhibited covers the entire year of 1777 and includes the important final text of the Articles of Confederation, the first written constitution of the United States. In 1777 the continental Congress ordered only 300 copies of the final revised Articles: “the printed copies of the Articles, in the form of a 26-page pamphlet, were delivered to the president of Congress on 28 November… With each state receiving only 18 copies of the Articles, printers in many states were prompted to create their own copies of the document” in late 1777 and early 1778. All of the early printings of the Articles of Confederation are extraordinarily rare and desirable. The first official Congressional printing, the 1777 Lancaster pamphlet, is virtually unobtainable. This first edition of the Dunlap Journals for the year 1777 (printed in early 1778) would be the second official Congressional printing of the final text of the Articles of Confederation, the signal document governing the United States of America from 1781 (when its ratification was completed) until the enactment of the Constitution of 1787 on March 4, 1789. - image courtesy of the Klos Yavneh Academy Collection

|

For 139 years, no national day honoring the flag was observed in the United States until Woodrow Wilson issued his Presidential Proclamation of 1916 establishing June 14th as U.S. Flag Day. It would not, however, be until August 1949 that June 14th would be officially established as Flag Day by an Act of Congress.

The 1777 Flag Resolution, as evidenced in the Journals of Congress, was meant to define a naval ensign (or naval national flag) and did not specify any particular arrangement, number of star points, nor orientation for the stars. Consequently, the archaeological and written evidence on the numerous flag designs is sketchy and it is unknown which design was the most popular during the the 1777-1789 US Founding period. The three most notable early 13-star arrangements are the Francis Hopkinson Flag, the Brandywine Flag, and the Betsy Ross Flag.

In 1785 The Society of Cincinnati replace its 13 star field with the United States Great Seal as evidenced by this Diploma Signed by Society Secretary Henry Knox and President George Washington.

The 1777 Flag Resolution, as evidenced in the Journals of Congress, was meant to define a naval ensign (or naval national flag) and did not specify any particular arrangement, number of star points, nor orientation for the stars. Consequently, the archaeological and written evidence on the numerous flag designs is sketchy and it is unknown which design was the most popular during the the 1777-1789 US Founding period. The three most notable early 13-star arrangements are the Francis Hopkinson Flag, the Brandywine Flag, and the Betsy Ross Flag.

|

| Painter John Trumbull (1756–1843) used Declaration of Independence Signer Francis Hopkinson's US Flag Design in his paintings of scenes of The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton, The Surrender of the British General John Burgoyne at Saratoga, and Major General Charles Cornwallis' surrender at Yorktown - Circa 1785-1822. |

During the Battle of Brandywine, this banner was carried by Captain Robert Wilson's company of the 7th Pennsylvania Regiment. The company flag is red, with a red and white American flag image in the canton.

There is no evidence to support the Betsy Ross legend of sewing the first flag from a pencil sketch given to her by Commander-in-Chief George Washington, or teaching him how a five-point star is more simply cut than a six. Betsy was one of a number of women who made flags, in a variety of styles, in Pennsylvania during the late 1770's; Benjamin Franklin and John Adams described the flag to the Neapolitan ambassador in 1778 as bearing stripes in red, white and blue! We do know, however, that Major Pierre Charles L'Enfant adopted the thirteen star circle flag in his June 10, 1783, Society of Cincinnati Diploma design.

|

Major Pierre Charles L'Enfant Society of Cincinnati Diploma design, June 10, 1783 - Image Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

|

In 1785 The Society of Cincinnati replace its 13 star field with the United States Great Seal as evidenced by this Diploma Signed by Society Secretary Henry Knox and President George Washington.

We also know that the New York Historical Society owns the oldest known variation of the round 13-star flag which was incorporated into the Pewterers' Banner that was flown by their delegation while they marched in NY's "Constitution of 1787" ratification parade in 1788.

|

New York Historical Society's Pewterers' Banner - image courtesy of the New York Historical Society

|

Finally, regarding the US Founding Flags, we do know that the story of Betsy Ross sewing the flag emerged during the Centennial Celebration festivities in 1876, and that the most popular thirteen-star flag of the ceremonies was an amalgamation of the Hopkinson and "Betsy Ross" designs. A copy of this centennial flag is included in the exhibit.

In 1795, the number of stars and stripes was increased from 13 to 15, reflecting the entry of Vermont and Kentucky as 14th and 15th states in the union. The Flag was not changed when subsequent states were admitted and with 18 states waging a second war with Great Britain, the 15-star, 15-stripe flag inspired Francis Scott Key to write his "Defense of Fort McHenry," now known as the U.S. national anthem, "The Star-Spangled Banner."

|

| Dr. Naomi Yavneh Klos, July 3rd, 2013, on the set of CBS Morning News explaining the origin of the United States Flag. |

It was not until April 4, 1818, that a plan was passed by Congress changing the flag to 20 stars, with a new star to be added when each new state was admitted, while the number of stripes was reduced to 13 to honor the original states. The April 4th Act is also found in this exhibit:

|

This image of An Act to establish the Flag of the United States, approved April 4, 1818 is taken directly from the Acts Passed at the First and Second Sessions of the Fifteenth Congress. This first edition, printed in Washington, by the Department of State in 1819 also includes: A resolution for the admission of Mississippi into the Union; An Act to establish the flag of the United States; An Act authorizing the President to occupy West Florida, west of the Perfido River; Act to provide for Illinois statehood; An addition to the 1808 Slave Act regarding importation of slaves "It shall not be lawful to bring Negroes, mulattos, etc... into the United States, from foreign place, in any manner whatever, with intent to hold them slaves;" Admission of Alabama and Illinois as states; An Act to allow use of the United States Navy to enforce anti-slave importation laws; A treaty with Sweden, Treaties with the following Indian nations - Wyandot, Senecas, Shawanees, Ottawas, Delawares, Pattawatamies, Chippewas, Menomenee, Ottoes, Poncarar, Cherokee, and Creek - image courtesy of the Klos Yavneh Academy Collection |

The Peace of Paris and the Treaty of 1763, was signed on February 10th, 1763 by the kingdoms of Great Britain, France and Spain, with Portugal in agreement, after Britain's victory over France and Spain during the Seven Years' War whose theater in North America was known as the French and Indian War. One year before this treaty, France ceded her Louisiana Territory to Spain in the Treaty of Fontainebleau but was this not publicly announced until 1764.

|

Exhibited is a March 1763 printing of one of the more significant documents of the 18th century, being "The Definitive Treaty of Friendship of Peace between his Britannick Majesty, the Most Christian King, and the King of Spain, Concluded at Paris, the 10th day of Feb., 1763...". Resulting from it, France gave up Nova Scotia, Cape Breton, the St. Lawrence River islands & Canada to the British. France gives to England all her territory east of the Mississippi River except New Orleans. France gets back their Caribbean islands of Guadeloupe, Martinique & St. Lucia. Spain is given back Cuba in return for territory in East & West Florida. Specifically Article VII states:French territories on the continent of America; it is agreed, that, for the future, the confines between the dominions of his Britannick Majesty and those of his Most Christian Majesty, in that part of the world, shall be fixed irrevocably by a line drawn along the middle of the River Mississippi, from its source to the river Iberville, and from thence, by a line drawn along the middle of this river, and the lakes Maurepas and Pontchartrain to the sea; and for this purpose, the Most Christian King cedes in full right, and guaranties to his Britannick Majesty the river and port of the Mobile, and everything which he possesses, or ought to possess, on the left side of the river Mississippi, except the town of New Orleans and the island in which it is situated, which shall remain to France, provided that the navigation of the river Mississippi shall be equally free, as well to the subjects of Great Britain as to those of France, in its whole breadth and length, from its source to the sea, and expressly that part which is between the said island of New Orleans and the right bank of that river, as well as the passage both in and out of its mouth: It is farther stipulated, that the vessels belonging to the subjects of either nation shall not be stopped, visited, or subjected to the payment of any duty whatsoever. The stipulations inserted in the IVth article, in favour of the inhabitants of Canada shall also take place with regard to the inhabitants of the countries ceded by this article. This lengthy document takes about five pages of the The Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Chronicle, March 1763, Sylvanus Urbanus, printed in London: D. Henry. -- Klos Yavneh Academy Collection |

This 1763 Treaty of Paris transferred the east side of the Mississippi, including Baton Rouge, Louisiana, which was at that time part of the British territory of West Florida. New Orleans on the east side remained in French hands. The newly acquired of Florida and Louisiana territory was too large to govern from one administrative center so the British divided it into two new American colonies separated by the Apalachicola River. British West Florida's government was based in Pensacola, and the colony included the part of formerly Spanish Florida west of the Apalachicola, plus the parts of French Louisiana taken by the British. It thus comprised all territory between the Mississippi and Apalachicola Rivers, with a northern boundary that shifted several times over the subsequent years.

|

Exhibited here is a 1763 Account of British Florida and Louisiana - with color map. The Florida Parishes (Spanish: Parroquias de Florida, French: Paroisses de Floride), also known as the North Shore region, are eight parishes in the southeastern part of the U.S. state of Louisiana, which were part of West Florida in the 18th and early 19th centuries. Unlike much of Louisiana, this region was not part of the Louisiana Purchase, as it had been under British and then Spanish control. The parishes are East Baton Rouge, East Feliciana, Livingston, St. Helena, St. Tammany, Tangipahoa, Washington, and West Feliciana. The United States annexed most of West Florida in 1810. It quickly incorporated the area that became the Florida Parishes into the Territory of Orleans, which became the U.S. state of Louisiana in 1812. There are three pages taken up with "Some Account of the Government of East and West Florida..." with great detail. In part: The forests abound with wild beasts, the plains with birds of various kinds, and the rivers with fowl and first; and in short, by best accounts that are not yet extant, there appears to be no want of necessaries and conveniences of life; nor is the climate so intolerably hot as to affect the health of those who may think fit to settle there. Cochineal and indigo are among the natural productions of this country; and ambergrife is found in abundance on the southernmost coasts. The native Indians of Florida are perhaps the handsomest people in America; their complexion is rather inclining to olive than copper; their eyes are black and piercing, their bodies robust and their limbs finely turn'd. Their women swim the rivers, climb trees, and are in general so remarkably swift, that racing among them is a favorite diversion. Before the Spaniards possessed themselves of Florida, the natives had a kind of a civil government, the traces of which they preserve to this day. They were divided into petty states, who generally warred with each other, and who still continue the same practice. The Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Chronicle, November 1763, Sylvanus Urbanus, printed in London: D. Henry. -- Klos Yavneh Academy Collection |

|

King George III, Monarch of the British North American Colonies including East and West Florida - Exhibited here is an Autograph letter signed discussing the design of the Theological Pivre Medal, the health of Elizabeth (his daughter), and his friend’s horseback riding: My Good Lord, Yesterday I received from Burch his design for the Reverse of the Theological Pivre Medal, think, I now communicate to you this only Alterations I have proposed is that the Anfs shall not appear so well finished but of ruder workmanship and the name of the University as well as the year placed at bottom as on the other Medal.We have had some alarm from a spasmatick attack on the breast of Elizabeth which occasioned some inflammation but by the skill of Sir George Baker She is now just fully recovered and in a few days will resume riding on horseback which has certainly this Summer agreed with her.

George III was born in 1738, son of Frederick, Prince of Wales and Augusta. He married Charlotte of Mecklinburg-Strelitz in 1761 and produced fifteen children. George was diagnosed with porphyria, a mental disease which disrupted his reign as early as 1765. George III succeeded his grandfather, George II, in 1760; his father Frederick, Prince of Wales, had died in 1751 having never ruled. In the 1763, the Treaty of Paris ended the War for Empire. George III held his colonial holdings and gained Canada, the Northwest Territory, East and West Florida in North America. George's plan of taxing the American colonies to pay for military protection for Britain led to the Revolutionary War in 1775. The colonists proclaimed independence in 1776, but George III continued the war until the American victory at Yorktown in 1781. The Treaty of Paris, signed in 1783, ensured acknowledgment of the United States of America as an independent nation and ceded Britain’s Northwest Territory to the new nation. In his 1783 Treaty with Spain, George III ceded East and West Florida back to the Spanish Empire. George’s political power decreased when William Pitt the Younger became Prime Minister in 1783. George reclaimed some of his power, driving Pitt from office from 1801-04, but his condition worsened again and he ceased to rule in 1811. Personal rule was given to his son George, the Prince Regent. George III died blind, deaf and mentally ill at Windsor Castle in 1820. www.kinggeorgeiii.com - Klos Yavneh Academy Collection |

|

Marriage Declaration of King George III dated July 8, 1761 that:I have, ever since my accession to the throne, turned my thoughts towards the choice of a princess for my consort …I come to a resolution to demand in marriage the princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg Strelitz; a princess distinguished by every eminent virtue.The London Magazine or Gentleman’s Monthly Intelligencer, July 1761, R. Baldwin, London - Klos Yavneh Academy Collection |

|

Queen Charlotte Sophia Monarch of the British North American Colonies including East and West Florida - Exhibited here is a Revolutionary War dated autograph letter signed by Queen Charlotte to her brother written in French on the 19th of February 1779 translated in full:Sir my brother. It is with great pleasure that I congratulate Your Majesty on the Birth of the Princess, that Riene your very lovely wife comes by the assistance of Divine Providence to put the World, and I share with Your Majesty the joy that this event causes you begging the Quite Powerful that it of a agene from days to days to fill the royal house with all kinds of Benedictions. With my perfect sincerities. Your good sister, Charlotte. At St. James, 19th February 1779. Charlotte Sophia of Mecklenburg-Strelitz Queen of Great Britain and Ireland, the wife of George III. She married George shortly after his accession to the throne, in 1761. When George III first received his young bride on September 9, 1761, at the garden gate of St James's Palace, he was supposedly taken aback by her lack of beauty. It became evident, though, that the pious and modest Strelitz princess soon conquered his heart and willingly submitted to his strong influence over her. In the first twenty-one years of her marriage Queen Charlotte gave birth to fifteen children, nine sons and six daughters. Their eldest son was the future George IV, born in 1762. In contrast to most European Royal houses George III and Charlotte had a harmonious marriage. Charlotte played a prominent, though reticent, role on the stage of European world history. As Queen of England and consort of George III she became an eyewitness of a turbulent age. -- Klos Yavneh Academy Collection |

Despite overtures by the Continental Congress, both the West and East Florida British Colonies remained loyal to King George during the American Revolution, and served as havens for Tories fleeing from the emerging United States.

In the Seven Years War (1756-1763), Spain had sustained serious losses against the British. The British had attacked and occupied two of Spain's key trading ports: Havana, in Cuba and Manila, in the Philippines in 1762. In the peace settlement of 1763 Spain recovered Havana by ceding Florida, including St. Augustine, which the Spanish had founded in 1565. The American Revolutionary War in 1776 provided Spain with the opportunity to reclaim the Florida in North America.

In 1776, New Orleans Governor, Luis de Unzaga, the New Orleans Territorial Governor Unzaga, concerned about overtly antagonizing the British before the Spanish were prepared for war, agreed to assist the Continental Army covertly. Financier Oliver Pollock brokered shipment of desperately needed gunpowder through New Orleans with Unzaga approval.

In March 1777, the Spanish court secretly granted the United States most favored nation status to the previously restricted port of Havana. Benjamin Franklin noted in his 1777 report that three thousand barrels of gunpowder were waiting in New Orleans, and that the merchants in Bilbao "had orders to ship for us such necessaries as we might want." By 1778 the British papers were reporting the tenuous position of the West Florida settlements and Spain harboring Continental Rebels, "Their headquarters is in New Orleans, from whence they send out their parties to pillage the English lands. No inhabitants remain on the plantations from the Natches downwards," in their London papers.

Spain followed the lead of the British governing West Florida and East Florida as two separate colonies but a border dispute soon arose with the United States.

Great Britain's Treaty with the US establish Florida's northern boundary at the as the 31st parallel north. Britain's 1783 Treaty with Spain establish no boundary and Spain maintained Florida extended north at least to the 32° 22′ boundary line established by Britain in 1764 after the Seven Years War. A dispute arose and the US delayed a treaty enabling the nation to grow stronger.

In 1794 British Ambassador Thomas Pinckney was appointed as Envoy Extraordinary to Spain to settle the North Florida border dispute. He negotiated the Treaty of San Lorenzo or the Treaty of Madrid, in San Lorenzo de El Escorial on October 27, 1795. Pinckney's Treaty defined the boundaries of the United States with the Spanish colonies and guaranteed the United States navigation rights on the Mississippi River.

The treaty set the western boundary of the United States, separating it from the Spanish Colony of Louisiana as the middle of the Mississippi River from the northern boundary of the United States to the 31st degree north latitude. The agreement put, for the first time, the lands of the Chickasaw and Choctaw Nations of American Indians within the new boundaries of the United States. The territory ceded by Spain in Pinckney's Treaty was organized by the United States into the Mississippi Territory in 1798.

In the Seven Years War (1756-1763), Spain had sustained serious losses against the British. The British had attacked and occupied two of Spain's key trading ports: Havana, in Cuba and Manila, in the Philippines in 1762. In the peace settlement of 1763 Spain recovered Havana by ceding Florida, including St. Augustine, which the Spanish had founded in 1565. The American Revolutionary War in 1776 provided Spain with the opportunity to reclaim the Florida in North America.

In 1776, New Orleans Governor, Luis de Unzaga, the New Orleans Territorial Governor Unzaga, concerned about overtly antagonizing the British before the Spanish were prepared for war, agreed to assist the Continental Army covertly. Financier Oliver Pollock brokered shipment of desperately needed gunpowder through New Orleans with Unzaga approval.

In March 1777, the Spanish court secretly granted the United States most favored nation status to the previously restricted port of Havana. Benjamin Franklin noted in his 1777 report that three thousand barrels of gunpowder were waiting in New Orleans, and that the merchants in Bilbao "had orders to ship for us such necessaries as we might want." By 1778 the British papers were reporting the tenuous position of the West Florida settlements and Spain harboring Continental Rebels, "Their headquarters is in New Orleans, from whence they send out their parties to pillage the English lands. No inhabitants remain on the plantations from the Natches downwards," in their London papers.

|

The London Chronicle, England, June 25, 1778 printing of British Captain Ayres’ March 1778 letter concerning the British West Florida Mississippi lands that includes eight current Louisiana Parishes. The letter reports in full:"A very unhappy event has lately happened in this country which will prove utterly destructive to the English settlements on the Mississippi...The defenceless state in which this country was left being without a soldier, or place of force,induced the rebels to send from Fort du Quesne a part in an armed batteau under the command of Captain Willing, seemingly with the intention of pillaging the plantations, and obliging the inhabitants to take oaths of neutrality; this party originally consisted of only twenty-five men, but by promises to the hunters and rovers on the bateaux, in the upper parts of the river, their number in French and English amounted to about 150 men on their arrival at the settlement of the Natches, there they contented themselves in imposing oaths of neutrality, and dispatched a canoe to seize the ship Rebecca, Captain Cox, at Manchac, and which they surprised in a fog; the arrival of this canoe gave time to the planters to transport their Negroes and movable effects to Spanish lands, before the rest of the rebels got down; on their arrival they seized on the Negroes of such natives of Britain as has neglected to send them off, they burned the houses on some plantations, and committed acts of cruelty and treachery that would dishonor the most savage nations. To some they offered security, on the condition of their returning to their habitations, and confirmed that security by written permission, exacting at the same time an oath of neutrality; those who were deluded fell victim to their rapacity; for in violation of the faith pledged to them, and on every principle of honour and humanity, their property was seized, brought to New Orleans and sold at Vendue. Their headquarters is in New Orleans, from whence they send out their parties to pillage the English lands. No inhabitants remain on the plantations from the Natches downwards. To complete their barbarity, there only remains the destruction of the cattle and houses, and it is said a party is dispatched on that errand. Humanity shudders at the horrible cruelty of these wretches. Fifty to which the inhabitants might have repaired, would have preserved this valuable colony to Britain; even now 200 would suffice to restore it, and extirpate the vermin that invest it. Our loss is not considerable, being only the lands, and the improvements we have made. It is to be hoped government will not utterly neglect us. In proportion to the number of inhabitants, there is no where a more loyal people: no man of any property or character has joined the rebels.” |

Less than a year later, the Treaty of Aranjuez, between France and Spain, was signed on April 12, 1779. France agreed to aid in the capture of Gibraltar, the Floridas, and the island of Minorca. In return, the Spanish agreed to join in France’s war against Great Britain.

On June 21st, 1779, after they had finalized their preparations for war, Spain declared war against Great Britain according to the Treaty of Aranjuez's terms.

In the Gulf Region, Bernardo de Gálvez, the energetic governor of Spanish Louisiana, immediately began offensive operations to gain control of British West Florida. In September 1779 he gained complete control over the lower Mississippi River by capturing Fort Bute and then shortly thereafter obtaining the surrender of the remaining forces following the Battle of Baton Rouge. He followed up these successes with the capture of Mobile on March 14, 1780, following a brief siege. He then began planning an assault on West Florida's capital, Pensacola, using the recently-captured Mobile as the launching point for the attack.

At the Battle of Pensacola (March 9th – May 8th, 1781), Governor Gálvez's Army won a decisive victory against the British the Spanish control of all of West Florida closing off any possibility of a British offensive into the western frontier of United States utilizing the Mississippi River.

The Spanish also assisted the United States effort in the crucial Siege of Yorktown in 1781. A year earlier the US Dollar, whose note's face boasted an exchange rate of one paper dollar for one Spanish Silver Dollar, collapsed. The Continental Congress, to stave the escalating hyper-inflation, passed a resolution increasing the exchange rate to $40 for one Spanish Silver Dollar.